Charlie Sanderson, Operation Overlord—D-day+

Chapter 2 Charlie Sanderson, excerpt from “My Father’s War: Memories from Our Honored WWII Soldiers”

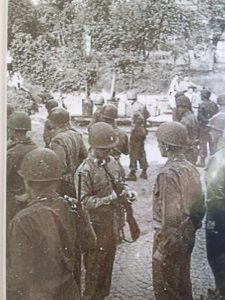

Sanderson eventually landed on Omaha Beach in Normandy, France. At that time, the Allies were only two miles inland, just about a week after the initial D-day invasion. His LST, which was designed to carry troops, supplies, and tanks across the water, was one of the first unloaded. Each LST had two or three trucks in it; the soldiers each carried half of a large gun as well as a carbine rifle, gas mask, and a few other needed supplies.

Sanderson had more than just the German Army to worry about. Another enemy was also waiting for him—water. Sanderson was worried because he had never learned how to swim. The water looked deep, the waves were crashing over the sides, the ship was rocking, and he was overloaded with weight like the rest of the troops.

Charlie Sanderson, less than twenty years old, didn’t know how to swim in an amphibious monster being dumped in vicious enemy territory, where it would be shot at and bombed. The Germans had various defenses on the beach, some similar to the Siegfried Line with six-foot-square concrete blocks staggered so you couldn’t drive a truck or tank between them, barbed wire, metal blockades, and plenty of mines. Those were the passive obstructions; the active ones were the Third Reich’s fortified troops shelling and bombing from above the beaches. Two miles back wasn’t very far for wartime fighting.

Barrage balloons were everywhere, their thick steel cables hanging down. The cables were intended to prevent aircraft from being able to fly low on their strafing runs. The aircraft unloaded thousands of rounds of gunfire as they flew low passes over the Allies, making headway up the beaches and onward. The balloons could go as high as ten thousand feet if needed, although they were used at a much lower level for this operation.

“Come in during high tide like a sitting duck, drop your ramp down, they yelled, ‘Sanderson, get your truck out … Go, go!’” Sanderson remembered. He was afraid, because he couldn’t swim. He also needed to know how deep the water was so the LST wouldn’t just flip over once the front gate was opened. He stuck a ten-foot-long stick into the water to gauge the depth and found the stick was not long enough. “I can’t go! I can’t go!” he screamed. “It’ll stand on its nose.” But they were yelling at him, “Go, go!”

Again, he said, “It can’t go. It’ll stand on its nose. I don’t want to drive the friggin’ truck over and tip it over. That’ll be the end of everything.”

They had to wait for the tide to come back out, playing sitting ducks again—strafing and shelling coming at them the whole time. They were unfortunate because, unbeknownst to them at first, they had stopped in a shell crater. That’s why the water was so deep around them where they’d stopped.

“The Germans didn’t know we were coming, but they were real smart. They were preparing for this for years,” Sanderson explained. “They’d have a swamp, for instance, and in it they had posts everywhere about ten feet high, knowing that someday gliders would be trying to invade and the gliders would crash into them. They were everywhere.”

Recalling his sights on the Normandy landing, he said, “When we came onto land, there were dead Germans and Americans everywhere. I noticed that the American officer had a one-inch white bar, three inches high, on the front and back of his helmet. Commissioned officers bars were going vertically, the noncommissioned officers were going horizontally. The Germans would use that as a target. You’d see the helmet with brains in it and busted open. You’d see the Red Cross on their arm, giving intravenous [treatments], and you’d see them both laying there, dead. They didn’t recognize Red Cross.”

“Aircraft started coming over, so many bombers coming over,” Sanderson said. “It would have been a nice, sunny day. Within two hours, it was hazy and dark from the smoke, dust, and whatever. So many would come and drop their bombs and head back. I honestly thought they were going back and refueling and coming back. They just couldn’t have had that many bombers coming in like that. It was just unbelievable—seemed like there was no end in sight to it. The sky was full of flak everywhere. You could hear the bombing, see a wing fly off or a tail fly off. It was dumbfounding, knowing those people were up there doing that and there wasn’t a damn thing those on the ground could do but just keep going. Just sitting ducks, like, ya know?”