Being A US Marine — WWII Fighting the Japanese

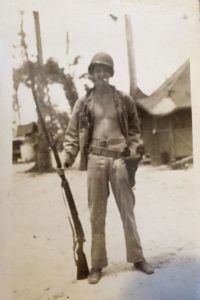

An excerpt from My Father’s War: Memories from Our Honored WWII Soldiers. Interviewed and written by Charley Valera. Featuring US Marine S/Sgt Albert Pinard.

On April 26, 1942 Albert G. Pinard turned seventeen years old. That same day he enlisted in the US Marine Corps for four years. Following are some details he shared of his life fighting the Japanese Imperial Army in the South Pacific Islands. From Iwo Jima, Okinawa and the Solomon Islands.

“There was a crew and myself, and we had one tent. We were waiting there while the rest of the guys went out on a mission. They never came back. I was alone in that damn tent for about two days,” Pinard remembered sadly. “Eventually, I was one of the last marines to leave Iwo Jima and head to Okinawa.”

In Rabaul, there were high volcanic peaks and low valley areas. Large winding, flowing rivers flowed between the peaks below, leading into a big harbor. The Japanese shipping was suffering from the army, navy, and marines’ constant barrage. “They were now using small boats to ship their supplies,” Pinard said. “They’d use these barges at night to supply all their different bases; they came out of Rabaul. These barges were thirty to forty feet long, made of steel, and armed to the teeth. There were many epic battles between them and our navy PT boats. They’d hide them during the day, camouflage them. But they were in the river, hundreds and hundreds of them,” he recalled.

“We wanted to kill their supply lines, so we went after those barges. Our mission was to come inland, come in between the mountains, strafe, and drop our bombs on those barges … Then it was off to sea. They had guns everywhere, shooting down at us, across at us, and up at us. To me, the most dangerous thing was, you’d have them shooting 90 mms, exploding shells, tracers, and all that, and they’re dangerous but better for high altitudes. As a dive-bomber, we’d have these Swedish design guns called Bofors with four barrels, a big round of ammo with clips of 40 mm. But when you came down on the deck, they’d be firing everything at us. They had 20s, 30s, 40s small arms, all shooting at us as we were going out between the peaks. At this mission there were army fighters, P-38s medium bombers … all kinds of flights, one of the bigger fights. A few hundred planes all going at this. But it was not very coordinated. They were all separate and going at the same time at the targets.

“The exciting thing on this was we knew we were going to be getting a lot of fire. We knew the gunners had to be ready, recover from the g’s, stand up, get over the side. A lot of times you’re shooting up ’cause they’re shooting down and there are tracers everywhere.

“Typically, when you’re on a mission, you have what they call radio silence. You don’t talk to each other over the radio because it helps the enemy radio-detection finders find you. They can home in on the radio waves and locate your position. You can talk to one another in your plane, but not to other planes—unless it’s a real emergency. When that was under way, the Japanese must have had a field day. You knew when a plane was going down because they were calling out ‘Mayday’ or another plane would be calling it out for them and where the approximate place the plane was going down.

“On that mission, I was firing the damn thing over the side and I had trouble with my ring at that time,” Pinard said feverishly, as if it had just occurred. “It wouldn’t lock into position, and every time I fired, the recoil would pull to the other side, and I thought I was going to shoot my tail. But I had to muscle it over the side. The pilot is yelling, ‘Over the other side … over the other side.’ I couldn’t see them. I was so busy myself and, at the same time, they had all these calls for Mayday, Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. I’m thinking, This many planes going down? I couldn’t see them myself. I was so busy myself.”

“On that mission, I was firing the damn thing over the side and I had trouble with my ring at that time,” Pinard said feverishly, as if it had just occurred. “It wouldn’t lock into position, and every time I fired, the recoil would pull to the other side, and I thought I was going to shoot my tail. But I had to muscle it over the side. The pilot is yelling, ‘Over the other side … over the other side.’ I couldn’t see them. I was so busy myself and, at the same time, they had all these calls for Mayday, Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. I’m thinking, This many planes going down? I couldn’t see them myself. I was so busy myself.”